Reese, a 17 year old female high school student, came out to her friends and family as bisexual a couple of years ago. Most of her family told her it was “just a phase” and now her friends ask her, “Are you sure you’re bisexual?” and “Are you still bisexual, you haven’t dated any girls?” These questions may seem innocent and inquisitive, but they dismiss Reese’s feelings and her friends are essentially telling her that doesn’t know herself. These questions and comments are microaggressions, intentional or unintentional insults, slights and/or derogatory questions and comments at target marginalized groups of people; in this case LGBTQ people.

Imagine if someone asked you, “How do you know you’re straight if you’ve never had sex?” Now imagine hearing this a few times a week, a few times a day. Would you start questioning yourself, who you are and doubting who you’re attracted to? Or maybe get really angry at the next person who asks you? These stigmatizations can stress you out and negatively impact your mental health.

Microaggressions can show up in three ways, microinsults, microassaults, and microinvalidations (Nadal et al, 2016). A microinsult is a comment or behavior that demeans a marginalized individual’s identity i.e. “You like watching football? But you’re gay!”.

A microassault is an overt insult or insulting behavior and can be verbal or nonverbal, like using “that’s so gay!” as an insult, and “no homo!” are very common microinsults.

A microinvalidation negates and dismisses an individual’s experiences or feelings. An example of a microinvalidation would be a straight friend minimizing an experience of discrimination that their queer friend disclosed. “You’re just overreacting, I’m sure your boss didn’t mean it like that” (Nadal et al, 2016). If you search for videos on microaggressions on YouTube, you’ll find more results that mock and minimize icroaggressions than ones that explain what they are. These are all examples of microinvalidations!

For LGBTQ folks who hear and see these these things every day, it adds up, and can give queer and trans folks the impression that the things that bother them don’t matter, or that they themselves don’t matter. This contributes to lower self-esteem, increased symptoms of depression, more binge drinking, and increased emotional reactivity (Nadal et al, 2016).

One of the hard things about microaggressions is that the person saying it and the person on the receiving end usually have very different perceptions of the conversation. Many microaggressions are accidental and someone may think they are giving a compliment (but it’s the kind that makes you roll your eyes, or feel kinda gross or uncomfortable), like “Are your boobs real? They look great!”

As an LGBTQ person on the receiving end, it can be hard to know why that comment made you so uncomfortable and you left that interaction feeling bad. You might wonder, “Was it because that person was being subtly transphobic or I am just being paranoid?”

Microaggressions are aimed at marginalized groups of people, most times you may not realize that what you say is offensive and why it’s offensive. They may be directed at someone’s culture/ethnicity “Your skin’s too light to be Mexican“, race “You don’t “talk Black”, nationality “You speak English so well”, sexual orientation “He’s my gay best friend!”, gender identity “You’re so lucky you don’t have to shave your legs anymore”, biological sex (to a woman in her late 30’s)“Why don’t you have any kids?”, ableism “You speak clearly for a deaf person” , social economic status (someone who grew up in a trailer park being told), “But you’re so smart!” It’s important to pay attention to what you say to everyone, and here we’re focusing on microaggressions that are specific to LGBT. I bet you’ve said something like this to someone and are now realizing that you used a microaggression. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7oHkF8YnJG0

Here are some examples of microaggressions targeted at:

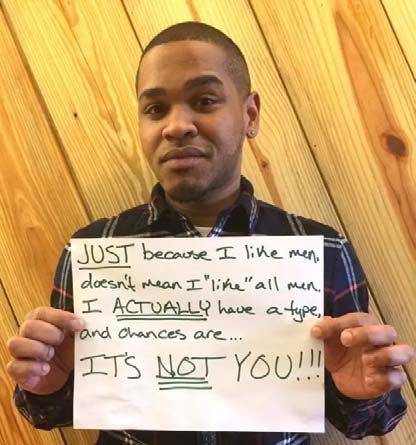

Gay Men:

“Oh! My best friend’s brother is gay too, maybe you know him?”

“God, I couldn’t even tell you are gay, you just look like a regular guy!

“All the good guys are taken or gay!”

Bisexuals

“Being bisexual is not a thing; you just can’t decide if you like girls or guys!”

“Did you go through a bi phase in college?”

“Oooh, you’re bi, my boyfriend has always wanted a threesome, will you hook up with us?”

Lesbians:

“I know you’re a lesbian, but can’t you be more feminine?”

“Why don’t you ever wear skirts?”

“So, who’s the guy in your relationship?”

“You just haven’t had a good man yet!”

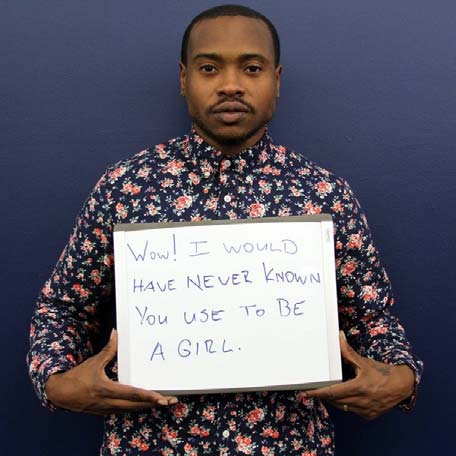

Transgender People

“You don’t look trans”

“Do you still have a dick?”

“What’s your real name?”

“Are you worried you’re going to want to ‘change back’ someday?”

“Are you a man or a woman?”

“I don’t know how you could mutilate your body like that!”

Assuming someone’s pronouns

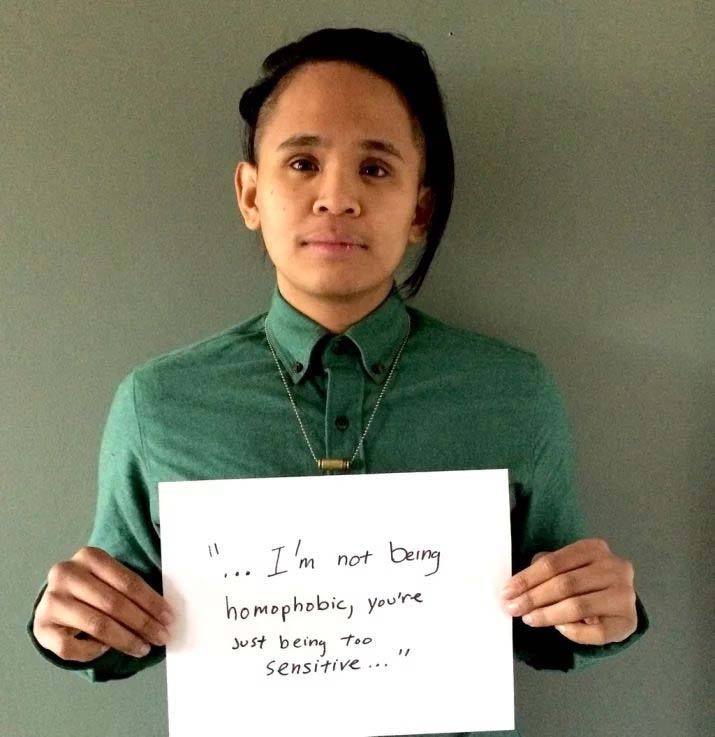

Perhaps, the worst microaggression of all is the denial of microaggressions! Often people’s reactions include, “Oh, you’re being too sensitive.”, “He didn’t mean it that way, you’re taking it wrong.”, “I am so sick of all this PC shit!” Acknowledging microaggressions forces people to stop and think, not just about what they are about they say, but how they feel about others who may be different than them. That’s work that a lot of people aren’t willing to do, they prefer to go along with the status quo.

What if I’m a microaggressor?!

Many microaggressions are not intended to be harmful by the people who say them, but there are a few tips to reduce the chance that you might unintentionally use microaggression with someone who identifies as LGBTQ:

- Don’t ask trans people about their genitals! It is intrusive to ask people you don’t know about their genitals. Period.

- Don’t use “gay” as an insult. It might make people who are gay feel invalidated, unwelcome, or unsafe.

- Don’t say “No homo!” It’s homophobic, and implies that there is something wrong with being homosexual.

- Don’t ask people how they have sex. Unless you’ve mutually decided that you are going to have sex with one another, how someone else has sex is not your business!

- Watch your assumptions. Just because you might be heterosexual, doesn’t mean everyone is. You can’t tell what pronouns people use just by looking at them – if you don’t know, ask! Just because you know two people who are genderqueer, doesn’t mean that you should set them up, or that they will like each other or have anything else in common. A queer person doesn’t need to have a same-gender partner in order to ‘qualify’ as queer.

Oh, no! I definitely messed up! What do I do now?

So what do you do if someone tells you that you’ve said something that is a microaggression?

First, take a moment to breathe. It can be hard to realize that you’ve messed up, and the urge to get defensive can be super strong. Slow down, take a breath before you react.

Second, listen. It often feels scary and risky for an LGBTQ person to confront someone about a microaggression, and they probably are worried about how you will respond. Chances are, if they feel uncomfortable about something that you’ve just said to them, other people have also felt uncomfortable when you’ve said the same sort of thing. This is just the person who was willing to say something to you about it. Here is an opportunity to learn how not to accidentally make LGBTQ people feel uncomfortable or insulted in the future…but only if you listen to them. This is a

lesson in how not to continue to be “that person”.

Third, believe them. One way guaranteed to make it worse is by telling them they are wrong for feeling how they are feeling. That is actually another microaggression! (Remember microinvalidations from earlier?) This is a moment to remind yourself that what you intended is less important than the impact that it had.

Fourth, apologize. Most people will trust you more and feel more comfortable around you if you admit that you messed up and apologize for it, than if you deny or justify it. Fifth, do better next time. Most people have all kinds of assumptions that they’ve been taught by society, family, school, peers, the media, and religion about sexuality, relationships, and gender. Sorting through and unlearning the problematic stuff is a work in progress for most people.

You can read actual microaggressions people experience posted at www.microaggressions.com.

By Jean Pappalardo and Noelle Clason

Nadal, K. L., Whitman, C. N., Davis, L. S., Erazo, T., & C, D. K. (2016). Microaggressions Toward Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Genderqueer People: A Review of the Literature. The Journal of Sex Research, 53 (4-5): 488-508.doi:10.1080/00224499.2016.1142495